Soft rot, rhizome rot

Pacific Pests, Pathogens and Weeds - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens & Weeds

Ginger soft rot (162)

Pythium species. Pythium myriotylum and Pythium aphanidermatum are two common species reported on ginger.

Pythium myriotylum is recorded from Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. In Fiji, it is highly pathogenic on ginger.

Ginger, taro (Colocasia), giant taro (Alocasia), Talo tanna or Taro Palagi (Xanthosoma), beans and capsicum are susceptible (see Fact sheet no. 44). Many kinds of seedlings are susceptible to a damping-off disease in the nursery (see Fact Sheet No. 47).

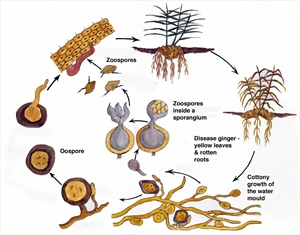

Pythium is not a fungus; it is an oomycete, related to algae. The common name is water mould. The water mould lives in the soil on roots of ginger and other crops, the remains of dead plants, on or in 'seed' (rhizomes) used for planting, and weeds. When conditions are not right for growth, the water mould produces thick-walled resting spores called 'oospores' (Diagram), and these can stay alive in the soil or in the rhizomes for a long time, waiting for a susceptible host to stimulate their germination.

The rot that occurs on ginger is typically a wet weather disease, influence by heavy rains after planting. Infection occurs when the water mould in the soil, or inside rots in the rhizome (the seed or planting piece), produces spores (Diagram). Swimming spores are formed inside larger spores and, when released, find their way to the fine roots, the young buds (or 'eyes') on the rhizome, or the junction of stem and rhizome. Damage to the rhizomes (Photo 1), roots and stems causes plants to yellow, and stems to collapse (Photo 2). At this stage, stems are easily pulled from the rhizomes.

Spread of the water mould occurs when the spores swim short distance in the water between soil particles, or are carried for longer distances in rainwater through the soil or over the surface. Neighbouring plants are infected, and patches of yellowing plants develop in the field. Spread occurs over long distances in Pythium-infected rhizomes used for planting.

Pythium myrotylum causes a serious disease. In Fiji, losses from soft rot are common, with 30-100% of the fields destroyed in the wetter parts of the country. The water mould can destroy rhizomes in 1-2 weeks. Impact of the disease is reduced if the crop is grown for immature ginger, and harvested early. However, losses still occur in the crop remaining in the field for seed, that is, planting material for the next crop.

Look for patches of unhealthy yellow, leaves. Look for dead roots and/or decay to large parts of the root system; look for rots on the rhizomes, especially at the buds.

CULTURAL CONTROL

Cultural control is particularly important in the management of this disease; in fact, it is the only practical way to manage it:

- Site and crop rotation:

- Site: Use small beds with deep drains or ditches around them if planting on flat ground or on a slope, so that the plants in the beds are isolated if soft rot occurs. It is best not to plant ginger down the slope below a field which had soft rot in the last crop. Rainwater can wash spores in the soil from 'diseased' fields to the new healthy crop.

- Crop rotation: Leave at least 4 years between ginger crops on the same land. Plant cassava, maize, and yam that do not suffer from soft rot.

- Source of seed: Choose seed only from areas without soft rot. Do not plant ginger obtained from neighbours unless the crop was monitored for soft rot; and never plant ginger bought at markets. If in doubt, seek advice from government agricultural services.

- Raised beds: Plant ginger on raised beds. Note what was said above about small beds and deep drains or ditches.

- Weeds: Keep weeds to a minimum, as many weeds are hosts of Pythium.

RESISTANT VARIETIES

None known.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Although regular applications of metalaxyl or phosphorous acid can control soft rot, the costs involved are likely to make ginger cultivation uneconomic, and cannot be recommended.

____________________

When using a pesticide, always wear protective clothing and follow the instructions on the product label, such as dosage, timing of application, and pre-harvest interval. Recommendations will vary with the crop and system of cultivation. Expert advice on the most appropriate pesticide to use should always be sought from local agricultural authorities.

AUTHOR Grahame Jackson

Infomration from Meenu G, Jebasingh T (2019) Diseases of ginger. (https://www.intechopen.com/books/ginger-cultivation-and-its-antimicrobial-and-pharmacological-potentials/diseases-of-ginger); and CABI (2014) Plantwise. Rhizome soft rot of ginger. (https://www.cabi.org/ISC/FullTextPDF/2015/20157800154.pdf); and Le DP et al. (2014) Pythium soft rot of ginger: Detection and identification of the causal pathogens, and their control. Crop Protection 65:153-167. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261219414002415?via%3Dihub); and from Diseases of vegetable crops in Australia (2010). Editors, Denis Persley, et al. CSIRO Publishing. Photo 1 Robert Fullerton, Plant & Food Research, Auckland, New Zealand.

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project PC/2010/090: Strengthening integrated crop management research in the Pacific Islands in support of sustainable intensification of high-value crop production, implemented by the University of Queensland and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community.