Sweetpotato Alternaria blight. It is also known by several other names: leaf and stem blight disease, Alternaria leaf and stem blight, Alternaria anthracnose. (Using the term 'anthracnose' for this disease can be confusing. This term is usually given to fungal diseases caused by Colletotrichum species - black spots on stems, leaves and fruits that produce masses of slimy pink spores under humid conditions.)

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides

Sweetpotato Alternaria blight (527)

Alternaria bataticola. Recent work using morphology and molecular sequencing in South Africa recognises several Alternaria species associated with blights on sweetpotato. Alternaria bataticola is recognised from Australia, Japan, South Africa, but so too is newly described Alternaria ipomoea (Ethiopia, South Africa), and Alternaria neoipomoea (South Africa). Another species, Alternaria argyroxiphii (South Africa), was previously described from another host.

Asia, Africa, South America, Oceania. The disease is important in Eastern and Central Africa (Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda), and also in Brazil. It is reported from Papua New Guinea.

Sweetpotato.

Recent studies have found that Alternaria blight of sweetpotato is caused by at least four species in South Africa, so it is likely that a similar situation exists elsewhere. S

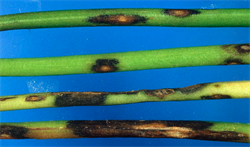

urveys in Uganda, for instance, would be particularly useful where the disease is particularly aggressive. Similarly, it would be of interest to check the identity of the disease in Papua New Guinea, previously identified as Alternaria bataticola. However, it appears that the disease caused by each of the four species is similar.At first, small dark brown to black oval spots occur on the fully-grown leaves showing a ring pattern. On the underside of the leaves the veins turn black. The spots grow up to 5 mm in diameter, frequently join together and are often surrounded by yellow haloes. Later, the infected leaves turn yellow and fall off. In severe cases, they create a carpet of dead blackened leaves over the soil. On petioles and stems, the spots are grey at first, later becoming black and sunken (Photos 1&2). If they grow right around the petioles and stems they kill them.

Alternaria species are not the only fungi that cause these symptoms. Reports from South Africa have shown that a disease similar to Alternaria blight was mostly associated with Phoma, another fungus. Phoma is a common soil-borne fungus that causes a pink rot of the storage roots, but had not previously been reported on vines in South Africa.

Spread over short distances is by airborne spores and is also carried on wind-driven rain. Over long distances the disease is spread on cuttings used for planting. High relative humidity is required for spore germination, infection and spore formation. Survival is in the soil on plant debris.

Most work on impact has been carried out in Uganda where the disease is especially serious. Yield loss depends on variety, region and cropping season. All commonly grown and preferred varieties are susceptible. The disease is most serious in crops at mid and high elevations, those in the cool, moist southwestern highlands (altitude above 1500 masl and annual rainfall 900-1350 mm), and in parts of the central Lake Crescent Region, but less so in the drier regions of eastern and northern Uganda.

In places where conditions favour the disease, losses of storage root yield of 50-90% are reported, especially where

Alternaria blight and sweet potato virus disease occur together. Such is the importance of these diseases that they are the focus of breeding programs at the National Crops Resources Research Institute, Namulonge, Uganda, in collaboration with the International Potato Center (CIP), Peru.Look for spots on the leaves, joining together and causing leaves to collapse and fall; look for spots on vines, black with greyish centres. There are no other foliar diseases of sweetpotato that are similar: virus diseases do not show black spots, and the fungal disease Elsinoe scab causes brown scabs along leaf stalks (petioles) and leaf veins, and tiny spots between them. The severe leaf distortions of scab are quite different from those of Alternaria blight (see Fact Sheet no. 13).

BIOSECURITY

The unrestricted movement of plant propagating material (cuttings, shoots and storage roots) has the potential of further spreading Alternaria blight. Many countries in Africa, Asia, South America and Oceania are yet free from the disease. The most likely pathway of entry is associated with unofficial transfers. For those that are officially sanctioned, follow the advice given in the FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sweet Potato Germplasm (http://www.bioversityinternational.org/e-library/publications/detail/sweet-potato/).

CULTURAL CONTROL

Selection and breeding of resistant or tolerant varieties is the main method of managing Alternaria blight, together with cultural practices of crop hygiene, involving the destruction of infected crop debris.

Before planting,

- Selection of planting material should be done carefully: remove old diseased leaves, and inspest vines for spots.

- If farmers want to ensure that planting material is free from the disease, do the following (possibly a method for commercial growers):

- Make a nursery on raised beds, shaded by coconut (or other) leaves, and plant washed sweet potato roots, leaving a small gap (1-2 cm) between each root.

- Cut vines 30 cm long from the roots as they sprout, checking each one to ensure that it is free from Alternaria blight leaf and stem spots. If present, discard the vine.

- Plant vines in new gardens, where sweet potato has not been grown for 1-2 years, as far from existing plantings as possible.

- Select varieties that have tolerance. Consult agricultural extension officers for those that are available locally (see under Resistant Varieties).

During growth:

- Weed. Alternative weed hosts have not been identified, but may exist, so assume weeds are a source of the disease and remove them regularly.

After harvest:

- Collect and burn or bury old vines, or compost them.

RESISTANT VARIETIES

If in Africa, and especially Uganda, check the availability of NASPOT varieties released from the country's breeding program; many of these have been distributed to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Apart from high yields and acceptable taste, some have been selected for their orange flesh and also for their resistance to sweet potato virus disease.

In 1999, NASPOT varieties 3, 5 and 6 were released. These were followed by NASPOT 7 to 11. NASPOT 11 is of most interest, a seedling selection from a farmer participatory breeding program, with acceptable storage root shape, high dry matter, good to excellent consumer acceptance and moderate to high field resistance to sweet potato virus disease and Alternaria blight. Two more, NASPOT 12 and 13, were released in 2013 with field resistance to sweet potato virus disease and Alternaria bataticola. Evaluation of varieties and breeders' lines have also been made in South Africa.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Chemical control is not an appropriate method of managing this disease. Although fungicides would be effective, they are too expensive for most smallholders and often they are unavailable. If required in commercial planting, frequently applied mancozeb or copper compounds would be suitable choices. In South Africa the mixture azoxystrobin-difenoconazole gave satisfactory control of the disease.

AUTHOR Grahame Jackson

Information from Adebola PO, et al. (2010) Molecular characterisation of Alternaria species of Sweet Potato and development of a host resistance screening protocol. Aspects of Applied Biology 96:309-313. (http://www.cabi.org.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/cpc/FullTextPDF/2010/20103346646.pdf); Ames T, et al. (1997) Sweet potato: major pests, diseases, and nutritional disorder. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. (http://cipotato.org/wp-content/uploads/publication%20files/books/002435.pdf); Mwanga ROM, et al. (2003) Release of six sweet potato cultivars (‘NASPOT 1’ to ‘NASPOT 6’) in Uganda. Hortscience 38(3):475-476. (http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/38/3/475.full.pdf); Mwanga ROM, et al. (2007) Release of two orange-fleshed sweet potato cultivars, ‘SPK004’ (‘Kakamega’) and ‘Ejumula’ in Uganda. Hortscience 42(7):1728-1730. (http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/38/3/475.full.pdf); Mwanga ROM, et al. (2011) ‘NASPOT 11’, a Sweet potato Cultivar bred by a Participatory Plant-breeding approach in Uganda. Hortscience 46(2):317–321. 2011.(http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/46/2/317.full.pdf); O’Sullivan J, et al. (Undated) Sweet potato DiagNotes: A diagnostic key and information tool for sweet potato problems. (https://keys.lucidcentral.org/keys/sweetpotato/key/Sweetpotato%20Diagnotes/Media/Html/TheProblems/DiseasesFungal/AlternariaStemBlight/Alternaria%20blight.htm); and from Woudenberg JHC et al. (2014)Large-spored Alternaria pathogens in section Porri doisentanged. Studies in Mycology 79: 1-47. (https://www.studiesinmycology.org/index.php/issue?start=12); and from Kandolo SD, et al. (2016) African Crop Science Journal 24(3): 331-339. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/acsj/issue/view/14556

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project HORT/2016/185: Responding to emerging pest and disease threats to horticulture in the Pacific islands, implemented by the University of Queensland, in association with the Pacific Community.