Bobone and taro vein chlorosis.

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides

Taro rhabdovirus diseases (089)

Viruses assoicated with these two rhabdoviruses are: i) bobone = Colocasia bobone rhabdovirus (CBDV) and ii) taro vein chlorosis = Taro vein chlorosis virus (TaVCV). There is evidence that TaVCV in Fiji and Samoa are different strains.

CBDV occurs in Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. TaVCV has been recorded from Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu.

These viruses have only been found in taro.

CBDV. In most varieties of taro the virus causes mild symptoms when alone. Small dark green distorted patches occur on one or two leaves before healthy leaves are produced (Photo 1). However, when CBDV occurs with other viruses it produces a lethal disease; in Solomon Islands growers call this disease alomae, and the susceptible taro are called 'male' are they are large).

A few lower-yielding varieties that resistant to alomae, but CBDV infection causes a severe stunting disease called bobone (Photo 2). These are the so-called 'female' taro of Solomon Islands, see Fact Sheet no. 01). Plants are grossly distorted with short, thickened, twisted leaves that stay green. Gradually, they recover and leaves look healthy.

CBDV is invariably present in plants with alomae, but whether TaVCV is also needed to cause alomae is not yet known. (See Fact Sheet no. 01 for more details on these diseases.)

TaVCV. The virus produces a yellow feather-like pattern similar to Dasheen mosaic virus (see Fact Sheet no. 88), but in the case of TaVCV, the yellowing is much brighter (Photos 3-5). Also, as the leaf ages the yellow lines turn brown (Photo 4). Symptoms of TaVCV often occur on plants with bobone and also with alomae (see above).

Spread of CBDV is by Tarophagus planthoppers, and spread of TaVCV is possibly the same(Photo 7). The planthoppers suck up the viruses when they feed on sap. The viruses multiply inside the planthoppers, and after 3-4 weeks they spread the viruses as they feed.

CBDV and TaVCV are also spread in other ways:

- From mother plants to suckers.

- By growers when infected planting material is taken from one garden to another.

On their own, the impact of CBDV or TaVCV on the yield of the taro varieties found commonly in Pacific island countries is thought to be small. Usually, only one or two leaves are affected before healthy-looking leaves develop. However, the impact of CBDV and other as yet unidentified viruses is severe. Entire plantings are destroyed very rapidly once alomae takes a hold.

The impact of CBDV on the few taro varieties that are resistant to alomae (in Solomon Islands and possibly Papua New Guinea) but are susceptible to bobone is much less. Corms of diseased plants are about 25% less than those that stay healthy, but not every plant develops symptoms, so overall yield is much less. However, there is an additional loss from growing 'female' taro: there is an opportunity loss involved in deciding tom grow lower yield, but alomae tolerant taro compared to those that are potentially higher yielding.

Look for leaves showing irregular, dark green thickened patches, or look for leaves that show more extensive, stunted green, twisted leaves; these are symptoms of CBDV. In both cases, plants should out-grow symptoms. Look for leaves showing bright yellow, feather-like symptoms along the main veins, and produce healthy leaves after one or two with symptoms (TaVCV).

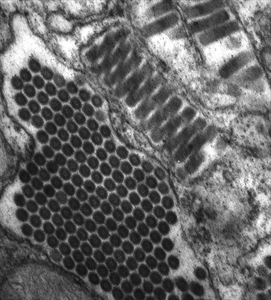

Under the electron microscope the particles of both viruses are rod shaped (Photo 6). Molecular tests are available based on specific primers for each virus.

NATURAL ENEMIES

Cyrtorhinus fulvus, a bug that feeds on the eggs of Tarophagus species (Photo 8), reduces the population of the plant hopper, but experience shows that it is not enough to stop the spread of alomae when Tarophagus populations are high (Photo 9).

CULTURAL CONTROL

At present, the cause of alomae is unknown; it can only be managed as follows:

- Do not grow 'male' and 'female' taro in the same garden; CBDV from plants with bobone may interact with other viruses to cause alomae in the so-called 'male' taro.

- Never plant taro next to gardens where alomae is present.

- If bobone occurs, mark plants with a stake; at harvest, cut off the corms, sell or eat them, and burn the plants and suckers. Do not replant them. (It is likely that roguing alone will not be sufficient and an insecticide is needed). In both Papua New and Solomon Islands, Derris species (fish poisons) have been introduced with high rotenone content sufficient to control Tarophagus). See information from agricultural authorities.

- If alomae occurs, remove the plants carefully (see Fact Sheet no. 01), and, if available, use chemicals to kill the planthoppers on the remaining plants (see below).

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Under commercial cultivation using the higher-yielding ('male') taro, regular application with a synthetic pyrethroid insecticides will kill Tarophagus planthoppers and prevent alomae. Good results are also likely if insecticides are used on the low-yielding ('female') taro, although in this case insecticides should be combined with removal of bobone-infected plants (see above).

____________________

When using a pesticide, always wear protective clothing and follow the instructions on the product label, such as dosage, timing of application, and pre-harvest interval. Recommendations will vary with the crop and system of cultivation. Expert advice on the most appropriate pesticide to use should always be sought from local agricultural authorities.

AUTHORS Helen Tsatsia & Grahame Jackson

Information from Lethal taro viruses - still unresolved. (https://www2.pestnet.org/other-pacific-plant-protection-stories/); and Carmichael A, et al. (2008) TaroPest: an illustrated guide to pests and diseases of taro in the South Pacific. ACIAR Monograph No. 132, 76 pp. (https://lrd.spc.int/about-lrd/lrd-project-partners/taropest); and Revill RA, et al. 2005) Incidence and distribution of viruses of Taro (Colocasia esculenta) in Pacific island countries. Australasian Plant Pathology 34: 327-331; and Shaw DE, et al. (1979) Virus diseases of taro (Colocasia esculenta) and Xanthosoma sp. in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Agricultural Journal 30: 71–97; and from Macanawai AR, et al. (2005) Investigations into the seed and mealybug transmission of the Taro bacilliform virus. Australasian Plant Pathology 34: 73-76. Photo 6 Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, UK.

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project PC/2010/090: Strengthening integrated crop management research in the Pacific Islands in support of sustainable intensification of high-value crop production, implemented by the University of Queensland and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community.