Western flower thrips

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides

Western flower thrips (183)

Frankliniella occidentalis

Asia, North, South and Central America, the Caribbean, Europe, Oceania. It is recorded from Australia and New Zealand, but not from any Pacific island country.

Wide; it has been recorded on more than 250 plants in 65 families, although it is not sure if it breeds on all these or just feeds on them. Some examples are: soft fruit (plums, peaches, strawberries, grapes); flowers (Gladiolus, Impatiens, Gerbera, Chrysanthemum, poinsettia); vegetables (cucumber, tomato, capsicum, cabbages, beans), both in the field and in greenhouses. Many species of wild flowers are hosts.

Damage is caused by thrips in two ways. Direct damage results from feeding. The adults and nymphs have modified mandibles that puncture the cells of flowers and leaves to release their contents which they then suck up. Foliage becomes silvery, leaves and flowers become flecked, spotted and deformed (Photos 1&2), buds fail to open, scarring occurs on fruits of capsicum, cucumber and beans, and undersides of leaves show small black specks of faecal material.

Indirect damage is caused by infection of crops by viruses. Thrips spread Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) (Photo 3). Symptoms of the virus vary with host, plant age, and temperature. The virus causes significant damage to vegetables in the Solanaceous family, such as tomatoes (Photo 3), potatoes and capsicum, but also lettuce. Many weeds, too, are hosts.

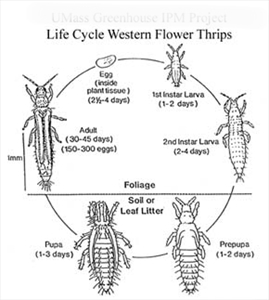

The eggs are kidney-shaped and laid in the flowers or leaves. The nymphs are pale yellow, thin and wingless, up to 1 mm long (Photo 4). They begin feeding immediately after hatching. There are two nymph stages. Towards the end of the second, the nymphs move down the plant to pupate in soil or in plant litter. There are two pupal stages and during this time the thrips are inactive and do not feed. Adults emerge a few days later; they are thin, ranging in colour from yellow through to light brown, 1.5-2 mm long, with two feathery wings (Photo 5). The life cycle varies from nine to more than 40 days in Australia, depending on temperature (Diagram).

All stages shelter in crevices or between touching leaves or flower parts. The length of the life cycle and life expectancy of the adults depends on temperature and also on the quality of the food. At 30°C the life cycle is about 12 days, while at 20°C it is about 20 days. The females live up to 90 days, whereas males live for about half that time.

Short distance spread is by flight; thrips are weak fliers, but often assisted by wind. Long distance spread is with infested plants associated with the horticultural trade or contaminated equipment.

Direct damage results in lost yield and/or inferior prices, as damage is unsightly - common in roses, strawberries, beans, capsicum and cucumbers.

Indirect damage by thrips as a vector of TSWV is common in lettuce, capsicum and tomato. TSWV is a tospovirus spread by western flower thrips, onion thrips (see Fact Sheet no. 117) and melon thrips (see Fact Sheet no. 106); however, the western flower thrips is the more important vector. TSWV has a very wide host range, and the only thrips that transmits the virus in a persistent way. This means that once the thrips picks up the virus through feeding, it retains it for life. Interestingly, the nymphs have to pick up the virus for the adults to be able to transmit it. Thrips need only a few minutes of feeding to transmit the virus.

Some countries have produced figures for the estimated costs of western flower thrips and TSWV. In the Netherlands, for instance, the annual cost of western flower thrips was put at US$30, with another US$19 million for TSWV. Furthermore, the estimated crop damage by all tospoviruses transmitted by western flower thrips exceeds US$1 billion per year.

Look for discoloured, deformed new growth and buds - when thrips feed on developing tissues, the cells are unable to expand and mature leaves and petals become distorted. Look for scaring on fruit, particularly noticeable on capsicum, and look for leaves which have a silvery appearance. Shake or tap flowers and shoots over white paper. Use yellow or blue sticky traps. Blue traps have the advantage that they are not as attractive to non-thrips species.

NATURAL ENEMIES

Natural enemies include Orius, Geocoris and Nabis species and also the larvae of lacewings, but all these are general predators. Also, predatory mites (Transieus and Amblyseius species) and predatory thrips (Haplothrips) are common, but do not adequately control thrips populations, except under greenhouse conditions, where they are used as part of IPM programs. They are commercially available in some countries.

CULTURAL CONTROL

Western flower thrips is more difficult to control than other thrips species because it develops rapid resistance to pesticides. Cultural control options aim to prevent infection and minimise spread.

Before planting:

- Check seedlings to ensure that they are free from symptom. It is best for farmers to raise their own seedlings, or source seedlings only from nurseries that are screened with thrips-grade mesh, and monitored for western flower thrips and TSWV.

- Remove weeds from within and around crops. Note that thrips and TSWV have very wide host ranges, including many weeds. Grasses, however, are poor hosts and could be used around greenhouses and nurseries to reduce the need for management of other weeds that are hosts. A 10 m strip around greenhouses and nurseries or around crops is sufficient. Bare ground is also effective.

- Do not plant new crops next to those infested by thrips; do not plant the same crop on the same land without a break: use a rotation; and do not plant new crops downwind from those infested with thrips. These measures are especially important if the "old" crop is infected with TSWV.

During growth:

- Monitor routinely for thrips. Use yellow or blue sticky traps placed about 10 cm above the crop, and inspect weekly.

- Rogue any plants showing symptoms of virus.

After harvest:

- Collect and destroy crop debris by burying or burning.

RESISTANT VARIETIES

There are resistant varieties of cucumber and tomato to TSWV.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

If thrips cause physical damage to the crop then insecticide sprays may be needed. However, there are problems using pesticides to control thrips. First, the insects are hidden within flowers and the leaves of shoots; secondly, the eggs are inserted into the leaves making it difficult for sprays to reach them; and thirdly, thrips rapidly become resistant to insecticides, so much so that there are large differences in the susceptibility of thrips populations to commonly used products.

Use insecticides as follows, but note that frequent use of broad spectrum synthetic insecticides may also lead to development of insecticide resistance in thrips populations:

- Use horticultural oil (made from petroleum), white oil (made from vegetable oils), or soap solution (see Fact Sheet no. 56). The spray will not kill all of the thrips, but it will suppress the population enough to allow predator and parasite numbers to build up and start to control them.

- Several soap or oil sprays will be needed to bring the thrips under control. It is essential that the underside of leaves and terminal buds are sprayed thoroughly since these are the areas where the thrips congregate. It is best to spray between 4 and 6 pm to minimise the chance of leaves and flowers becoming sunburnt. Test the soap and oils on a few leaves or flowers.

- White oil:

- 3 tablespoons (1/3 cup) cooking oil in 4 litres water.

- ½ teaspoon detergent soap.

- Shake well and use.

- Soap:

-

Use soap (pure soap, not detergent).

- 5 tablespoons of soap in 4 litres water, OR

- 2 tablespoons of dish washing liquid in 4 litres water.

-

- White oil:

- Commercial horticultural oil can also be used. White oil, soap and horticultural oil sprays work by blocking the breathing holes of insects causing suffocation and death. Spray the undersides of leaves; the oils must contact the insects.

- Use neem to discourage adults from feeding and laying their eggs on the plants (see Fact Sheet no. 56).

- Do not use broad-spectrum insecticides such as dimethoate (under review in Australia, and not allowed for use in home gardens), malathion and permethrin. They have a greater effect on the natural enemies of western flower thrips than on the thrips.

____________________

When using a pesticide (or biopesticide), always wear protective clothing and follow the instructions on the product label, such as dosage, timing of application, and pre-harvest interval. Recommendations will vary with the crop and system of cultivation. Expert advice on the most appropriate pesticide to use should always be sought from local agricultural authorities.

AUTHOR Grahame Jackson

Information from CABI (2020) Frankliniella occidentallis (western flower thrips). Invasive Species Compendium. (https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/24426); and Western flower thrips. Plant Health Australia. (https://www.planthealthaustralia.com.au/pests/western-flower-thrips/); and from DPIRD (2016) Chemical control of western flower thrips. Agriculture and Food. Government of western Australia. (https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/fruit/chemical-control-western-flower-thrips). Photo 1 T Smith, University of Massachusetts.Bugwood.org. Photo 2 L Pundt, University of Connecticut. Photo 3 William M Brown Jt., Bugwood.org. Photo 4 Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org. Photo 5 Jack T Reed, Mississippi State University. Bugwood.org. Diagram Life cycle western flower thrips. University of Massachusetts.

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project PC/2010/090: Strengthening integrated crop management research in the Pacific Islands in support of sustainable intensification of high-value crop production, implemented by the University of Queensland and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community.