Ironwood tree decline (IWTD). On Guam, it is also known as IWTD disease syndrome; this is to suggest that IWTD results from more than one cause acting together.

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides

Casuarina tree decline (544)

A disease associated with two pathogens, bacterial wilt, Ralstonia solanacearum, and Ganoderma australe; the involvement of the termite, Nasutitermes takasagoensis, was also considered to be involved in spreading the disease, but now this is thought unlikely.

Under a revised classification system (2005), and based on DNA sequencing, Ralstonia solanacearum has been divided into four groups, reflecting geography (phylotypes), and further by genetic sequence of an important gene (sequevars). By this method the strain of Ralstonia solanacearum infecting Casuarina in Guam is phylotype 1 (Asia). It is equivalent to biovar 3 on the system that separates strains on their use of certain carbohydrates.

Asia (China, India), Africa (Mauritius), Oceania. It is recorded from Guam.

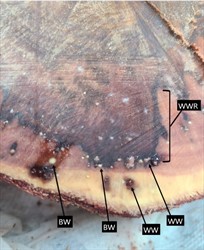

Casuarina equisetifolia

Since 2002, surveys have detected a slow decline of Caruarina trees on Guam. A thinning of foliage, tip dieback of branches and death occurs on trees ranging in age from 10 years to several decades (Photo 1). Two major plant pathogens have been found associated with the decline: Ralstonia solanacearum and Ganoderma australe. When cut, trunks of trees with slow decline show wetwood symptoms: dark stained centres radiating outwards, oozing off-white droplets of Ralstonia solanacearum at their margins and other wetwood-rot species, e.g., Klebsiella (Photo 2). In addition, a large proportion of the trees with IWTD have fruiting bodies of the fungus Ganoderma australe (Photo 3).

Cross sections of trees with IWTD in Guam are like those reported from China with infections of Ralstonia solanacearum. However, in China, and in also in India, decline occurs in plantations where 100% of the trees with symptoms yield Ralstonia solanacearum. There, the time from initial symptoms to death is rapid, weeks to months in China and weeks in India, whereas in Guam it is months to years. The other difference is that Ralstonia solanacearum is present in only 65% of trees with IWTD in Guam. It is concluded that Ralstonia solanacearum is the major cause, with Ganoderma australe also playing a part, but independently of the bacterium - one survey showed 27% of the trees with the fungus were negative for Ralstonia solanacearum, although they had severe decline.

Spread of IWTD has sought a role for the termite, Nasutitermes takasagoensis. Termites chew on tree roots and in the process may transfer Ralstonia solanacearum bacteria from one tree to another, but spread this way seems unlikely. It is more likely to occur from root-to-root contact or by water moving within the soil.

The impact of the decline is not well documented in Guam, but the importance of Casuarina is well acknowledged: it is able to withstand salt spray, cyclone-force winds, and limestone soils of high pH. In Guam, the tree is planted as a windbreak, for erosion control along beaches, in soil restoration projects, as a shade tree in urban settings, and for its foliage which is used as a mulch. It occurs naturally as a component of secondary forests.

Look for trees with slow decline. Severity can be measured using a set of images that have been published in Guam with varying levels of bare branches and loss of foliage. Thorough diagnosis requires destructive sampling of the trees, cutting the trunk to look for: (i) the area of wetwood, and (ii) ooze from the sapwood-heartwood transition zone (white viscous) or from the sapwood transition and heartwood zones (watery amber).

Look for the termite, Nasutitermes takasagoensis, and Ganoderma australe fruiting bodies. These are likely indicators of IWTD.

Note, monoclonal antibody test strips are available to detect Ralstonia solanacearum. They detect the species but cannot differentiate race or biovar. Samples for testing (shavings) are extracted by drilling into the trunks, stems or roots of trees showing symptoms.

BIOSECURITY

Bacterial wilt is a very difficult disease to control once established for several reasons: (i) the bacterium can remain alive in the soil without a host for about 9 months; (ii) the bacteria can survive for several years in host debris; (iii) the bacteria have a wide host range, infecting many crops and weeds; and (iv) the bacteria can live on the roots of some plants without infecting them or causing symptoms.

Countries still free from bacterial wilt, but vulnerable to its introduction, need to: (i) define risk and pathways; (ii) have preventive measures in place; (iii) enact quarantine protocols in case a breach occurs; and (iv) be able to action a rapid response against the bacterium in case eradication is a possibility.

CULTURAL CONTROL

Before planting:

- Ensure seedlings are raised free from bacterial wilt, preferably in soilless composts or pasteurised soil, in clean pots or reusable plastic seedling propagation trays.

- Avoid planting in compacted soil, or soils with poor drainage, aeration or water holding capacity. Where such soils cannot be avoided add copious amounts of organic matter to maintain healthy growth.

During growth:

- Organic amendments and mulch

- Provide conditions for adequate growth, such as organic amendments to increase root growth to lessen transplanting shock and the effects of drought.

- Mulch with Casuarina needles, 2-3 cm deep (or alternative organic material), to conserve water, suppress weeds, and lower soil temperatures.

- Hygiene

- Remove trees with signs of IWTD as soon as seen, preferably excavating as much of the root system as possible to prevent spread of pathogens via root-to-root contact.

- Remove trees damaged by storms or disease; excavate rather than sawing trunks at ground level, to prevent colonisation and spread of soil-living, wood-rotting fungi.

- Tree maintenance

- Prune trees to remove deadwood that might otherwise allow colonisation by termites or wood-rotting fungi.

- Sanitise tools (use bleach) between working on one tree and then another.

- Do not damage roots with lawnmowers or weed trimmers.

RESISTANT VARIETIES

Seed from Australia has been imported in recent years to increase the genetic diversity of Guam's Casuarina.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Not a method to use in the management of IWTD.

AUTHOR Grahame Jackson

Information from MERSHA Z et al. (2011) Decline of Casuarina equisetifolia (ironwood) trees on Guam: Ganoderma and Phellinus. Phytopathology 101 S206. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304025455_Decline_of_Casuarina_equisetifolia_ironwood_trees_on_Guam_Ganoderma_and_Phellinus); and Schlub RL et al. (2011) Decline of Casuarina equisetifolia (ironwood) trees on Guam: Symptomatology and explanatory variables. Phytopathology 101: S206. (https://www.apsnet.org/meetings/Documents/2011_Meeting_Abstracts/s11ma51.htm); and Schlub RL et al. (2020) Ecology of Guam's Casuarina equiseltifolia and research into its decline. In: Haruthaithanasan M et al. eds. Proceedings of the sixth international Casuarina workshop: Casuarinas for green economy and environmental sustainability. Krabi, Thailand; 21-25 October 2019. IUFRO Working Party. Kasetsart Agriculture and Agro-Industrial Product Improvement Institute. p. 237-245.(https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_journals/2020/rmrs_2020_schlub_r001.pdf); and University of Guam (2020) UOG researchers work to stop ironwood tree decline in Guam. (https://www.uog.edu/news-announcements/2020-2021/2020-uog-researches-work-to-stop-ironwood-tree-decline.php); and Schlub RL (Undated) Pathogens linked to the decline of Casuarina equisetifolia (ironwood) on the Western Pacific tropical island of Guam. Extension & Outreach, College of Natural and Applied Science, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam. (https://www.uog.edu/_resources/files/extension/publications/Pathogens_Linked_Decline_Ironwood.pdf); and Schlub RL (2019) Gago, Guam Ironwood Tree. Past, Present, Future. University of Guam, Guam Cooperative Extension. (https://docslib.org/doc/6468625/gago-guam-ironwood-tree-casuarina-equisetifolia-past-present-future-guide-guam-ironwood-tree-manual); and Fegan M, Prior P (2005) How complex is the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex,” in Bacterial wilt disease and the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex, ed. C. Allen, P. Prior and A. C. Hayward (St. Paul, MN: APS), 449–462; and from Garcia RO, et al. (2018) Ralstonia solanacearum species complex: A quick diagnostic guide. Plant Health Progress 20: 7-13. (https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/10.1094/PHP-04-18-0015-DG). Photos 1-3 Robert Schlub, Emeritus Professor of Plant Pathology. College of Natural & Applied Sciences, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam .

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project HORT/2016/185: Responding to emerging pest and disease threats to horticulture in the Pacific islands, implemented by the University of Queensland and the Secretariat of the Pacific.