Med fly

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides

Med fly (506)

Ceratitis capitata

Asia, Africa, North (Hawaii), South & Central America, Europe, Oceania. Note, its presence in Asia is mainly confined to the Middle East, not further east than Iran. It is present in Australia (Western Australia only), but absent from the Ord River irrigation area. It is not present in any Pacific island country.

A wide range of fruit, vegetables and nuts are hosts. Important commercial crops include, apple, bell pepper (capsicum), citrus, cocoa, coffee, guava, olive, quince, stone fruit (apricot, cherry, lychee, mango, nectarines, peaches, plums, and others). There are wild hosts in several plant families.

Med fly is a severe pest with more than 200 hosts, many of them important commercial crops; it poses a threat to numerous countries (from temperate to tropical), either because of its presence or because of their vulnerability to its introduction. The threat is expected to increase with climate change. The first sign of damage are the marks left on unripe or ripening fruit when adults lay eggs, the so-called 'sting' typical of tephritid fruit flies.

Eggs are laid in batches of one to 10, 300 in a lifetime; they are white, slender, just visible to the naked eye. As they are laid, bacteria are inserted which rot the flesh and provide food for the larvae. Eggs hatch in 2-4 days in temperatures over 12oC and below 28oC, and the larvae spend 6-11 days in the fruit, growing to about 8 mm, before developing into 4 mm long pupae in the soil. Another 6-11 days later adults emerge. However, where temperatures are below 12oC, the pupal stage lasts up to 50 days, with adults emerging from the soil in the warmer spring temperatures.

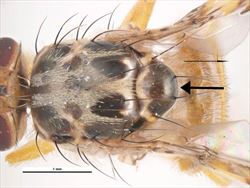

The adult body is 3.5-5 mm long - slightly smaller than a housefly (Photo 1). The thorax has black and yellowish (sometimes silverish) patches and a mostly black scutellum (Photo 2). The abdomen has two light bands on the bottom half (Photo 3) Wings have a wide brownish-yellow band across the middle, and other black, brown and brownish-yellow markings (Photos 4&5). Adults live for 2-3 months, longer in cooler climates. The length of life cycles vary considerably, reflecting the different climates within the Med fly distribution.

Males gather in groups (called lekking) at dusk, emit pheromones, and 'sing' - a buzzing noise made with their wings to attract females.

Spread occurs by flight. Med flies are considered weak fliers, and do not disperse more than a few hundred metres if food is plentiful, unless carried on the wind; however, there is a report of dispersal of over 20 km. Larvae spread in infested fruit, principally associated with the trade in agricultural produce and in fruit carried (illegally) across borders or sent in the mail.

CABI suggests that Med fly is the single most important pest species in its family (Tephritidae). As with other fruit flies, infestations result in crop losses, loss of export markets, and/or costly treatments to ensure compliance with quarantine measures imposed by importing countries. If treatments involve the use of pesticides then higher costs of production impact farmers' incomes, as well as risks to their health and the environment.

In Mediterranean countries, citrus and peach are severely damaged and there, as well as elsewhere, fruit crops can be totally destroyed by Med fly. But it is not only fruit crops that are at risk: in Central America, for instance, coffee is attacked, with losses estimated between 5-15% due to reduced quality - infested berries mature earlier and fall to the ground.

Emergency eradication programs have proved costly, and very unpopular with the public where they rely on area-wide insecticide applications. Alternative strategies have been sought. In California, for instance, Med fly has been eradicated several times to save the fruit industry, estimated to be worth $1.5 billion a year. The last in 1994 used areawide SIT (instead of pesticides) and was so successful that it was continued as a preventive program after eradication was achieved, irrespective of cost. Likewise, South Australia has introduced a program to protect the state from Med fly introductions from Western Australia.

Look for black and yellowish (possibly silverish) patches on the thorax, two light bands across the abdomen, and yellowish-brown bands across the wings. Med flies have a pair of characteristic hairs with flattened tips arising from the inside of the eyes (Photo 1). Females differ from most other species by the yellow wing patterns, and the shiny black lower half of the scutellum (Photo 2).

Eggs and larvae of Med fly are similar to those of Queensland fruit fly (see Fact sheet no. 425). However, the Queensland fruit fly is larger, reddish brown with clear wings. Because of the similarity of this fruit fly to others, it is important that specimens are examined by a specialist familiar with fruit fly taxonomy.

BIOSECURITY

Countries not yet infested by Med fly should consider all likely pathways for entry, and apply quarantine measures accordingly. Fruit and vegetables may need to be treated to manage risk of fruit fly introduction by, e.g., high-temperature forced-air, low temperature, insecticide dips, irradiation (although not accepted by most countries), hot-water treatment, area freedom, or area-wide management. Where Med fly is established but not uniformly distributed, or where countries are free from Med fly, but close to those infested, they may wish to consider biosecurity provisions which limit the free movement of produce known to harbour Med fly within their own borders. In this connection, even if Med fly populations are detected but are not permanent, quarantines treatments may be demanded by countries not yet infested.

Med fly is on the EPPO A2 list, as it is present locally in Europe and recommended for regulation as a quarantine pest. It is of quarantine significance to the Caribbean, North American and Asia-Pacific plant protection organisations.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL

Waterhouse & Sands concluded that those parasitoids attacking the fly in Hawaii - Fopius arianus, Fopius vandenboschi, Diachasmimorpha longicaudata, Psyttalia incisi, and others - are doing so only because of the presence of the more recently introduced oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, which acts as a reservoir/alternative host for parasitoids. Introductions attempted before the arrival of the oriental fruit fly failed to establish. Similarly, when the first four parasitoids listed above were introduced in relatively large numbers into Western Australia for the control of Med fly, they also failed to establish. This supports the idea that another, preferred, host was needed. Further searches of biocontrol agents within the native range of Med fly within Africa were suggested.

CULTURAL CONTROL

The most effective control strategies for this fruit fly are: i) monitoring; ii) crop hygiene and iii) protein-bait sprays.

Before planting:

- Mostly a pest of tree crops, so this does not apply.

During growth:

- Monitor (scout crops twice a week):

- assess fresh damage caused by fruit fly attack:

- check fallen fruit, cut open and check for fruit fly maggots. Check also for egg-laying 'stings' on the surface of fruit

- use traps with i) trimedlure to attract male flies and ii) Biolure Unipak (ammonium acetate, trimethylamine hydrochloride and putrecine) to attract females; the traps may contain an insecticide.

- Place traps 1.5-2 m from the ground in shady parts of trees in pairs(male and female lures) at least 25 m apart, one trap (at least) per ha. Change ingredients every 2 and 3 months in male and female traps, respectively.

- note, the traps are not for controlling the fruit fly, but only to detect its presence.

- assess fresh damage caused by fruit fly attack:

- Crop hygiene:

- use nets or bags for individual fruits when used after fruit set (especially useful for home gardens). Curtain mesh is ideal. The net must have a weave of about 2 mm x 1 mm to prevent entry by fruit flies. Make sure the net is not touching any fruit or they may lay eggs through the net, and so are brown paper bags. Brown paper bags or newspaper can also be used, although it may not last long in high-rainfall areas. As the method is labour-intensive, commercial growers should check whether it is economically viable. The bags or net sleaves must be applied before the fruit is susceptible to attack, which in most cases is prior to fruit colour-break. However, some fruit, e.g., melons and solanum crops are susceptible to attack at the immature, green stage.

- use netting (mosquito, shade-cloth, etc.) to enclose trees when fruit is ripening (remove afterwards). Branches can also be individually netted.

- collect and dispose of prematurely ripened fruit, fallen and overripe fruit, and fruit left on the tree

After harvest:

- A number of methods can be used to destroy the remains of harvests:

- collect fruits left on trees, shrubs, vines, etc., bury them deeply in the soil, along with compacting the soil to squash the insects.

- destroy crop residues by boiling or burning.

- place infested fruit in plastic bags, seal carefully, and leave in the sun for a few hours to kill the maggots, or freeze them for at least 24 hour.

- Collect and destroy remains of harvests, especially fruit left on trees, shrubs, vines, etc., by crushing the fruits with a boot, ploughing into the soil, boiling or burning. Small numbers of fruit can be placed in black plastic bags, left in the sun for a few hours to kill the maggots, or frozen for at least 24 hour.

- After cooking the fruit it can be fed to livestock (e.g., pigs and poultry).

- Do not compost or put infested fruit in garbage bins. The remaining plant debris can be used as a mulch or incorporated into soil.

ERADICATION

The have been many attempts at eradication of Med fly. This is usually attempted by (i) defining a quarantine area around the outbreak site, (ii) control of fruit movement, (iii) removal of fruit on infested crop and collecting and destroying fallen fruit, (iv) protein bait and insecticide sprays (to attract and kill male and female flies), (v) management of green waste, and vi) male annihilation technology (high density traps, up to 400 per km2), containing sex pheromone plus insecticide). Sterile insect technology (SIT) is frequently applied together with protein bait sprays.

SIT has been used for the eradication of Med fly in Australia, Africa (South Africa), North (USA, Mexico), South (Argentina, Brazil, Chile), and Central America (Costa Rica, Guatemala, Nicaragua), Africa (South Africa), Middle East (Jordan), and Europe (Italy, Portugal, Spain).

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Cover sprays over the entire crop have given way to protein bait sprays with insecticides that are more economical, and less hazardous in the environment.

- Use a protein bait (e.g., yeast autolysate from brewery waste) with an insecticide (e.g., malathion or spinosad in Australia; spinetoram or fipronil in other countries) to control both male and female fruit flies. There are two methods of application:

- Baits - apply as spots or bands on stems, trunks, branches or foliage, when the fruit is susceptible (varies with the crop, see below). Apply the mixture as a course spot-spray (60-100 mm diameter) to each tree. It can be applied with a hydraulic knapsack sprayer, hand held sprayer, or even with a course brush to flick large droplets onto foliage. Re-apply weekly, and after heavy rains.

- Lure & kill traps - similar ingredients as baits (i.e., protein and insecticide), but traps are hung from trees, attracting male and female flies. Re-place liquid weekly into clean traps.

- Starting & stopping - bait when fruit is susceptible, from fruit set for melon and solanum crops, half size for other fruits, and continue until final harvest and removal of crop residues.

- Home-made sprays and traps for back-yard fruit trees (without insecticides) should follow the recipes provided (see Fact Sheet no. 507).

____________________

When using a pesticide, always wear protective clothing and follow the instructions on the product label, such as dosage, timing of application, and pre-harvest interval. Recommendations will vary with the crop and system of cultivation. Expert advice on the most appropriate pesticides to use should always be sought from local agricultural authorities.

AUTHORS Graham Walker & Grahame Jackson

Information from Waterhouse DF, Sands DPA (2001) Classical biological control of arthropods in Australia. ACIAR Monograph No. 77, 560 pp.; and CABI (2020) Ceratitis capitata (Mediterranean fruit fly) (https://www.cabi.org/cpc/datasheet/12367); Broughton S (Undated) Fruit fly monitoring in commercial orchards. Agriculture and Food Division, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. Government of Western Australia. (https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/medfly/fruit-fly-monitoring-commercial-orchards). and Broughton S (Undated) Controlling Mediterranean fruit fly in orchards: mass trapping and attract-and-kill devices. Agriculture and Food Division, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. Government of Western Australia. (https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/medfly/controlling-mediterranean-fruit-fly-orchards-mass-trapping-and-attract-and-kill-devices); and Broughton S, McCarthy A (Undated) Mediterranean fruit fly life cycle & biology. Agriculture and Food Division, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. Government of Western Australia. (https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/medfly/mediterranean-fruit-fly-life-cycle-biology); and The Australian Handbook for the Identification of Fruit Flies (2018) Plant Health Australia. Canberra, ACT. (Version. 3.1). (https://www.planthealthaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Australian-Handbook-for-the-Identification-of-Fruit-Flies-v3.1.pdf); and from Yates. Fruit fly control in your garden (https://www.yates.com.au/plants/problem-solver/pests/fruit-fly/). Photos 1-5 Walker K (2006) Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata). Museum of Victoria: PaDIL - http://www.padil.gov.au. Diagram McDougall S, et al. (2013). Tomato, capsicum, chilli and eggplant: A field guide for the identification of insect pests, beneficials, diseases and disorders in Australia and Cambodia. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). (http://aciar.gov.au/files/mn-157/index.html).

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project HORT/2016/185: Responding to emerging pest and disease threats to horticulture in the Pacific islands, implemented by the University of Queensland and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community.