Sweetpotato whitefly, tobacco whitefly, silverleaf whitefly

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides - Online edition

Pacific Pests, Pathogens, Weeds & Pesticides

Sweetpotato whitefly (284)

Bemisia tabaci. There are a number of closely related strains (or biotypes) that appear the same as the local strains, but can only be identified by molecular techniques. The two most important are the silverleaf, MEAM1 or B biotype, and the Q or Mediterranean (MED) biotype. The B biotype is also referred to as a different species, Bemisia argentifolii, and more species may be named in the future from within this group. Both spread many viruses, and are resistant to many insecticides.

Previously, tropical and sub-tropical countries, but now distributed widely as the whitefly has become a glasshouse pest, although parts of Europe are still whitefly-free.

Surveys in the late 1990s, recorded four biotypes in Oceania:

- the B biotype (Bemisia argentifolii) recorded from Australia, American Samoa, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, and USA (Hawaii).

- the Nauru biotype, recorded from American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Samoa, Tonga, and Tuvalu.

- the Australasian biotype, from the northern half of Australia, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Niue, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu.

- the Q biotype recorded only from Australia.

Originally, Bemisia tabaci had a narrow host range in the tropics and sub-tropics, feeding on cassava, cotton, sweetpotato, tobacco and tomato. But with the appearance of the silverleaf B biotype in the 1980s, the host range widened to more than 500 species, including many vegetables - beans (and other food legumes, including peanuts), capsicum, cucurbits (especially watermelon and squash), lettuce, papaya - ornamentals, poinsettia in particular, and a large number of weeds. The Q biotype has a similar wide host range.

Damage occurs in several ways: (i) the whiteflies have piercing mouthparts, and suck sap from the leaves removing nutrients, turning the leaves yellow, causing them to fall early and generally weakening the plants; (ii) whiteflies produce honeydew as they feed on plant sap, and this is excreted in large amounts onto the foliage. It contains sugary substances favoured by sooty mould fungi, and the leaves and stems turn black, reducing sunlight (see Fact Sheet no. 51); (iii) the B and Q biotypes produce toxic reactions in zucchini, squash, melon and tomato, spoiling their appearance; and (iv) whiteflies are very efficient at spreading viruses that cause severe diseases.

More than a hundred virus diseases are spread by this whitefly, among which begomoviruses (previously called geminiviruses) are some of the most important, causing, for example, African cassava mosaic virus, Cotton leaf curl virus, and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. The latter is one of the most important tomato diseases worldwide, although not yet recorded from Pacific islands.

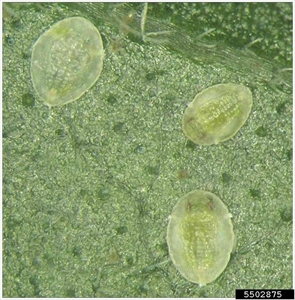

Eggs are laid in small groups on the underside of leaves; they are white at first, later brown (Photo 1). The first stage nymphs have legs and antennae, and are mobile; they are known as 'crawlers'. Later, they settle down, become pale yellow-green, flat, and scale-like, and pass through three more stages, the last is called a 'puparium' - the hardened skin of the third stage (Photo 2). When the adults emerge, they are a little over 1 mm long, yellow, with white waxy wings (Photos 3&4). The life cycle is completed in about 18-28 days, depending on the temperature, with the females living about two weeks, and laying up to 300 eggs.

The silverleaf B biotype is a major concern. It develops faster than the sweet potato strain, produces a greater number of off-spring, has a wider host range, is responsible for more sooty mould development, and induces a silverleaf disorder in tomato and cucurbits, squash in particular.

Both the B and Q biotypes have developed resistance to many insecticides.

Spread over short distances occurs with the movement of the crawlers, and the flight of adults. Over long distances, spread is by wind, and on plants distributed in the international trade in ornamental plants and cut flowers.

In general, local strains of Bemisia tabaci are a minor threat to crop production. They have been managed successfully by a combination of control measures, including the use of insecticides. However, in recent years, new biotypes have arisen which have become major pests. They impact on crop production by (i) breeding faster; (ii) spreading more viruses; (iii) infesting more plant species; (iv) rapidly developing resistance to insecticides; and (v) in some cases, causing toxic reactions in plants, or promoting sooty moulds, reducing growth or effecting quality.

On cotton, the whitefly honeydew makes it difficult to gin, i.e., separate the fibres from the seed.

The effect of viruses is especially acute, with lost yields of cotton amounting to many millions of dollars annually in India and Pakistan, and in tomato production worldwide. Epidemics of African cassava mosaic virus and, more lately, Cassava brown streak virus, where yield losses of up to 25% have been reported in East African countries, continue to cause crop failures, and threaten food security.

Look for plants (especially at the margins of fields) with sooty moulds and/or silver leaf symptoms (on tomatoes and cucurbits). Look for whiteflies taking flight when foliage is shaken and immediately settling on the undersurfaces of the leaves. Look for insects with brilliant white wings, held tent-like over the body, but slightly apart when at rest so that the yellow body can be seen between them. Look on the undersides of the leaves for the stationary nymphs and puparia.

QUARANTINE

Biosecurity authorities should take note of the risk that this whitefly presents to crop production, especially the silverleaf B and Q biotypes, consider pathways for their introduction, and ensure that regulations are adequate to prevent them becoming established. Assessments of the risks of introduction of this whitefly should include its ability to spread large numbers of plant viruses, many of which are extremely damaging to their hosts. To reduce this risk, authorities might consider the need for area-freedom of the more important whitefly biotypes and the viruses present where consignments originate.

NATURAL ENEMIES

Natural predators include lacewing larvae (see Fact Sheet no. 270), big-eyed bugs (Geocoris spp.) (see Fact Sheet no. 370), ladybird beetles (see Fact Sheet no. 83), the larvae of syrphid (hoverflies) flies (see Fact Sheet no. 84), and predatory mites. They attack the immature stages of whiteflies. There are parasitoids, too, tiny wasps that are natural biological controls of whitefly populations. Species of Encarsia and Eretmocerus are those most successful, and some are commercially available for use in greenhouses. Eretmocerus attack both the sweet potato and silverleaf B biotypes, and are effective at higher temperatures.

CULTURAL CONTROL

Before planting:

- Use reflective polyethylene mulches on planting beds; these repel whiteflies, and slow their build up by several weeks. The mulches are effective until foliage covers more than 60% of the surface.

- Use squash, cantaloupe melon or cucumber as trap crops, especially for the control of silverleaf B biotype, where tomato is the main crop, and there is a threat from infection by Tomato yellow leaf curl virus.

- Inspect seedlings in nurseries to ensure they are free of whitefly before transferring the plants to the field. If whiteflies are present, apply treatments as suggested under Chemical Control below.

- It is important to remove weeds before planting susceptible crops; weeds can be important sources of whiteflies and viruses.

During growth:

- Monitor crops using yellow sticky traps. Alternately, agitate plants to encourage adults to fly by shaking the plants.

- Continue to remove weeds from within and around cropping areas; this is extremely important for the reasons mentioned above.

- Remove infested leaves or, if practical, hose plants with water in the early stages of population development.

After harvest:

- Collect and dispose of the remains of the crop by burning.

- Do not plant new crops of the same kind next to older ones where whiteflies are present, especially if they are infected with Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. It is also important not to plant different crops favoured by whiteflies near each other.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Broadspectrum insecticides such as pyrethroids (e.g., deltamethrin, lambda cyhalothrin, bifenthrin), neonicotinoids (e.g., imidacloprid) and organophosphates (e.g., chlorpyrifos) should be avoided, as repeated use promotes the development of resistant populations of whiteflies, and will also destroy natural enemies. Resistance to insecticides is a particularly serious problem in the control of the silverleaf B and Q biotypes, which have become resistant to a wide range of insecticides.

If insecticides are required, do the following:

- Use horticultural oil (made from petroleum), white oil (made from vegetable oils), or soap solution (see Fact Sheet no. 56). The sprays will not kill all of the whiteflies, but will allow predators and parasites to increase and bring the whitefly infestation under control. Frequent applications (every 3-5 days) and good coverage is required.

- Several soap or oil sprays will be needed to bring the whiteflies under control. It is essential that the underside of leaves and terminal buds are sprayed thoroughly since these are the areas where the whiteflies congregate. It is best to spray between 4 and 6 pm to minimise the chance of leaves becoming sunburnt.

- White oil:

- 3 tablespoons (1/3 cup) cooking oil in 4 litres water

- ½ teaspoon pure hand soap, not detergent

- Shake well and use.

- Soap:

-

Use soap (pure hand soap, not detergent):

- 5 tablespoons of soap in 4 litres water.

-

- White oil:

-

Commercial horticultural oil can also be used. Note, these sprays work by blocking the breathing holes of insects causing suffocation and death. They are less likely to kill natural enemies as they are quickly broken down in the environment, and also the development of resistance to them is less likely than is the case when using synthetic pesticides.

-

Alternatively, use plant-derived products, such as neem, derris, pyrethrum and chilli (with the addition of soap). (For the use of neem and chilli see Fact Sheet nos. 402, 504, respectively; for derris see Fact Sheet no. 56.)

-

Or, use insect growth regulators that are used commercially for the control of this whitefly.

-

Or, microbial insecticides, synthetic products derived from microorganisms, such as abamectin and spinosad.

-

Synthetic pyrethroids are likely to be effective, but will also kill natural enemies.

--------------------

Note, derris (Derris species) contains rotenone, an insecticide, often used as a fish poison; it should be used with caution. The commercial derris insecticide is made from Derris elliptica.

____________________

When using a pesticide (or biopesticide), always wear protective clothing and follow the instructions on the product label, such as dosage, timing of application, and pre-harvest interval. Recommendations will vary with the crop and system of cultivation. Expert advice on the most appropriate pesticide to use should always be sought from local agricultural authorities.

AUTHOR Grahame Jackson

Information from CABI (2020) Tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci), and Silverleaf whitefly (Bemisia tabaci (MEAM1)). Invasive Species Compendium. (https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/8927 & https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/8925); and Silverleaf whitefly. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Queensland Government. (https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/agriculture/plants/fruit-vegetable/insect-pests/silverleaf-whitefly). and from De Barro PJ et al. (1998) Distribution and identity of biotypes of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in member countries of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community. Australian Entomological Society 37, 193-287. Photo 1 Lesley Ingram, Bugwood.org. Photo 2 Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org. Photo 3 Scott Bauer, USDA Agricultural Research Service. Photo 4 Richard Markham, ACIAR, Canberra.

Produced with support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research under project PC/2010/090: Strengthening integrated crop management research in the Pacific Islands in support of sustainable intensification of high-value crop production, implemented by the University of Queensland and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community.